What exactly constitutes a person’s will and values?

In my opinion, a person’s will is a desired end that reflects his values and internally justified by a clear rationale. There are two distinct parts here, the alignment of values and the justification. Both must be present for a desired end to be considered a person’s will. Let’s start with the first part. What exactly are a person’s values?

Values are a person’s ranked priorities – almost always intangible. One’s actions typically reflect one’s values. Each choice implicitly favors one outcome over all others, which endorses one value over another. And naturally, the things that a person would overwhelmingly prefers over the others would constitute his “core values.” It follows that a person’s true will is a desired end that reflects his core values.

Let’s look at some examples where a person’s actions reveal their values. No judgment here; purely illustrative:

- Bob decides to lie to his wife about his infidelity. He values sexual pleasure and the stability of his marriage over honesty and doing right by his wife.

- Abby steals some food so that she can feed her children. She values the wellbeing of her children over the sanctity of personal property.

- Albert leaves his well-paying but exhausting job to travel the world for a year. He values his own happiness above his career ambitions.

- Jesse orders the steak instead of the lobster. I leave this silly example here to show that values are really not so different from taste.

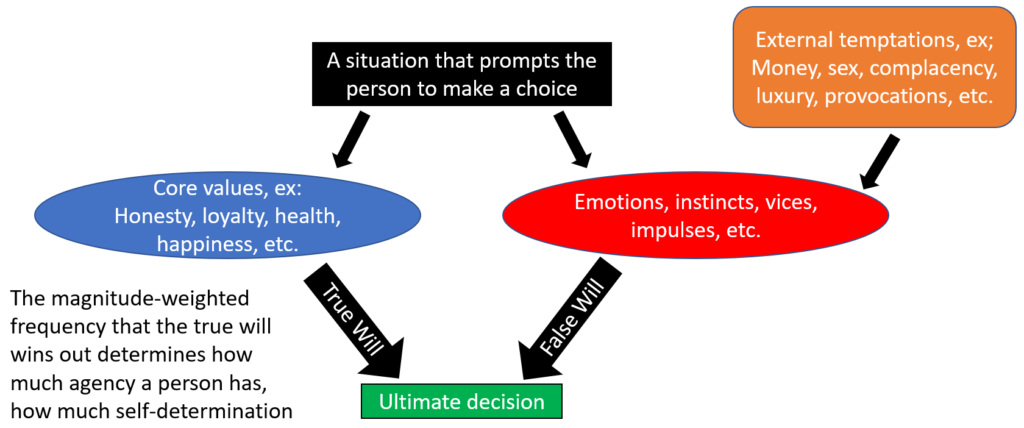

Further down, I’ve included a graphical illustration of how values and true will relate to judgment. Recall the angel and devil who would materialize on either shoulder of a cartoon character when he faces a moral dilemma. Normally, the “devil” would represent temptations, while the “angel” would argue for the more righteous decision, presumably aligned with the character’s core values.

- First, a situation presents itself to the moral agent, who then must make a choice. A moral agent’s core values are almost always compatible with virtues, since virtues are invariably linked to long-term wellbeing, or eudaimonia, as Aristotle described. I will expand on this later.

- Based on the core values, the true will prescribes an action or desired end that aligns with thereto. Notice how the true will is not unduly influenced by external factors.

- On the other hand, external temptations incite the emotions, instincts, vices, and impulses; the moral actor is also drawn in another direction, away from his true will.

- Those conflicting desires clash until one wins out to manifest as the ultimate decision by the moral agent.

- A person’s agency is determined by the magnitude-weighted frequency that the true will wins out against the false will. In other words, how often he can make the right decisions in the moments that really matter.

- The conventional definition of “willpower” refers to the exertion it takes for someone to actively resist temptations and thereby the false will.

Oftentimes, distinguishing true and false will can be difficult. But first, let’s examine a very clear-cut example:

Suppose John is a chain-smoker, consuming a pack of cigarettes a day. He knows perfectly well how detrimental cigarettes are to his life, be it his physical/mental health, his financial stability, his personal hygiene, etc., yet he cannot control himself due to his nicotine addiction. In this case, John clearly wills to quit smoking, yet he cannot due to the pain of withdrawal symptoms, i.e. external factors.

Next, let’s look at a more ambiguous example:

Suppose Maria has a social media addiction, particularly Instagram. She gets a high off of other people commenting and liking her photos, so she cultivates an image of her life far superior to reality. To that end, she travels not for enjoyment, but to take “Instagram-worthy” photos for her online following, getting a dopamine boost by inducing envy in others. Does Maria have agency? No. Her actions are driven more by the fickle opinions of others than her opinion of herself. She merely responds to external stimuli rather than being the playwright of her own life.

“Wait a minute,” you might argue, “who are you to say that Maria’s true will isn’t pleasing other people? What if she just values popular appeal more than you do? Don’t impose your set of values on her!” While I understand this perspective, it is myopic in scope. Suppose a 7-year-old child says that he wants to run away from home after his parents told him to go to bed, because his parents are too strict and bossy – would anybody claim his true will is to live on his own? The kid’s emotions run hot, and he can barely think clearly. In other words, he doesn’t know any better. Don’t tell me you’ve never had this line of thought – he’ll regret it down the line!

I believe that should Maria make an honest effort at introspection, to reexamine her own priorities in life and to consider her long-term mental wellbeing, she would realize that she doesn’t value other people’s (let alone strangers’) opinions above her own desires. When Maria is in her 60’s, would she come to regret her younger self’s obsession with chasing popularity? I believe so. While I have no way to empirically prove it, I think as people age, they tend to realize what truly matters to them, and the opinions of faceless strangers on the internet certainly do not rank at the top of the list.

Ultimately, a person must define his own values. Complicating the matter is the fact that people often do not even know what truly matters to them until they feel the full weight of the consequences of their actions. It’s said that people reflect on their life most clearly on their deathbed – they tend to reevaluate their past decisions with the grand perspective of time, probably the most “objective” way to determine whether or not someone has lived willfully, according to his core values. And thus, to live life without regret means recognizing your core values so that your true will drives your judgment rather than emotions, instincts, and impulses.

Distinguishing true and false will

As I’ve mentioned earlier, often, people aren’t aware of their core values, which are largely subconscious. To discern one’s core values requires an honest effort at introspection, which can prove extremely difficult for even the brightest minds. A person must let go of his ego and truthfully examine the justifications behind his actions and whether or not he has fooled himself.

Let’s consider one of the most classic examples of when a man mistakes external temptations for his core values: the investment banker. Could there be examples of when people genuinely enjoy the work, the long hours, and the sacrifice of their personal lives and relationships? Perhaps, but I’d wager it’s not the case for the vast majority of people. While I know it’s difficult to feel sympathy for them, please bear with me for the sake of the argument.

Brandon is a second-year associate at an elite investment bank. It took him a lot of effort to get here – he had to network like crazy, learn Microsoft Excel inside out, pull countless all-nighters and weekends, etc. Was it worth it? Did he truly get what he wanted? Of course, if one asks him directly, he’ll almost certainly respond in the affirmative. But how might Brandon justify his decisions?

- “Being an investment banker is a validation of my professional and thus personal worth.”

- “A big paycheck also makes me feel superior to those who make less money. It gives me bragging rights.”

- “I’m the living embodiment of the mantra that hard work pays off.”

- “If I throw in the towel now, it just means I’m a quitter, who isn’t willing to work hard.”

- “If I quit now, all my effort in the past 5-6 years would have been for naught.”

What are the benefits of being an investment banker?

- High pay

- Possible transition to buyside to get higher pay

- Expensed dinners(?)

- Personal validation(?)

- Bragging rights(?)

What are the downsides of being an investment banker?

- Romantic relationship suffers (if it exists)

- Familial relationships suffer

- Platonic relationships suffer

- Long hours

- Chronic sleep deprivation

- Inability to truly disconnect from work

- Mental/emotional health problems (potentially long-term)

- Physical health problems

- Much of work can be quite meaningless (making spreadsheets or presentations no client ever reads), which crushes self-esteem

Unsurprisingly, turnover is extraordinarily high for investment banking jobs. Bright-eyed, ambitious young professionals eagerly start their careers in high finance, lured by promises of high pay, professional success, and an ego boost, without grasping the sacrifices required. Eventually, however, many find that the costs don’t outweigh the benefits – perhaps Brandon will come to that realization as well? Perhaps at this point in his career, Brandon wonders what that high income is even for; he already has more or less any material possession he covets, and he lives otherwise quite comfortably. The personal/professional validation and bragging rights might have helped him endure the long hours and endless stress at the beginning. “Maybe prestige just isn’t worth this price?” he wonders.

One Friday afternoon, Brandon anxiously glances at the clock in anticipation. He’s already finished his work in preparation of his planned vacation, but he needs to stick around a bit longer for facetime. In about 30 minutes he’s heading for the airport on a long-awaited trip – an opportunity to finally reconnect with his old college buddies. The staffer had already given him the OK; everything is in order. Brandon worked several all-nighters this and last week to wrap up a deal, so this trip will help him unwind.

The seconds slowly tick away… until Brandon sees the notification for an email from a managing director. “pitch deck for company XYZ on my desk by tmrw morning,” demanding a week’s worth of work in less than 24 hours. That’s when Brandon realized that he could never truly breathe easy as an investment banker.

The old saying goes, “you never know how much you will miss something until it’s gone,” and that’s particularly true for one’s core values. One tends to take for granted good physical/emotional/mental health, relationships, sleep, and rest until one is deprived thereof. If Brandon eventually decides to quit, we can confidently assert that those considerations are part of his core values or at the very minimum, more important to him than high pay and prestige.

You could say that Brandon learned it the hard way – perhaps he could’ve avoided the whole situation had he been more honest about it in the first place. Some questions he should’ve asked himself before committing to the investment banking career track are:

- What am I REALLY doing this for? Is it for my own sake or for something superficial like prestige and the approval of others?

- Am I measuring my self-worth exogenously, e.g. in monetary value?

- 30 years from now, will I regret this decision?

- Do I truly understand the price I’m paying?

- What has been the experience of others who’ve made the same decision?

I believe that almost every instance of when someone has come to regret a major life decision was attributable to underappreciating one’s core values or overvaluing external temptations.

What do people typically regret in their old age?

- Not taking enough risks, be it professional or otherwise. People can get really comfortable in their complacency. And that cozy temptation of laziness could often override their ambition and innate desire for self-fulfillment.

- Not making peace with a relative. Perhaps due to ego or pettiness, feuds can last way longer than they should for trifling reasons.

- Not wisely choosing their romantic partner. It’s often due to a fear of being alone or lust that people decide to marry, and that fear could prove enough to trump values like fidelity or love.

- Not taking care of their own health. Bad health-related decisions typically come home to roost in old age, so it’s little surprise that gluttony, laziness, or addictions could supersede the value of health earlier in life.

Do core values change over time?

That’s impossible to know for sure. I wager that they might change modestly over time, but they largely remain the same throughout a person’s life. People tend to intuitively know what the right choice (the one aligned with their core values) is at any given juncture, even if they intentionally select an alternative, evidenced by the gnawing tinge of regret at the edge of their consciousness, often immediately after making a “wrong” decision. I don’t believe the reverse is true, that people would feel the same lingering doubt when picking the “correct” decision.

“What if I had swallowed my ego and just apologized?” “What if I had made that career change that I always dreamed of?” “What if I had taken that chance?” “What if I had told her how I feel?” These sorts of questions arise both immediately after submitting to the false will. A man might fool his conscious self, but he cannot fool his subconscious – the popular saying “trust your gut” really just means to “your subconscious is more honest and truer to yourself than your conscious mind.”

In other words, unless you’ve come to forgive yourself, any major decision for which you’ve experienced immediate ambivalence and pangs of regret, you’re likely to feel the same but more intensely at the twilight of your life.

Could a person’s values include vices?

This is another difficult question to answer, since nobody has a perfectly understanding of their own psyche, let alone someone else’s. Is it possible for someone to have, for example, money and power as their core values? I believe those are merely the means to ends, but who am I to say that there doesn’t exist anyone who lived their whole life regretless, having derived genuine happiness from the mere accumulation of money and power? I could argue that in an alternate universe, that individual would be far better served pursuing more important things like family and companionship, but that would require assuming the conclusion.

Psychopaths and politicians are strong contenders for being exceptions to the generalization that core values are virtuous. When lying comes as easily as breathing for them, one wonders if they even believe in the value of human virtues at all. One thing I know for sure, however – I have no intention of ever associating with anyone whose core values include vices or exclude virtues.

On a side note, I’m aware that to believe that most people’s core values are compatible with virtue, if not outright virtuous, would require the concurrent belief that people are good by nature and can be redeemed. However, the obvious caveat is that people are very easily led astray by powerful temptations and poor upbringing.

Reconciling values and pleasure

What about pleasure and the pursuit thereof? Those don’t broadly count as vices. What about hippies and other hedonists? For that, I take an Epicurean perspective, drastically different from the conventional understanding of “hedonism.” Typically, when one overindulges in pleasures, especially those of the body or artificially produced (drugs, for instance), one tends to regret later in life those liberties taken.

On the other hand, the ideal life according to Epicurus would be epitomized by the simple life of a fisherman living happily in a small village, enjoying a peaceful existence surrounded by family and good company. If one craves the simple pleasures of life, then one should set aside lofty career aspirations in favor of following one’s passions. I’d argue that this form of pleasure could qualify as a value; in fact, the vast majority of people probably hold said pleasure as a core value. For now, let’s refer to this as “happiness.”

What differentiates happiness from the hedonistic pleasure? This topic probably deserves an entire book’s worth of analysis, but I’ll try to distinguish them from a high level. Let’s bifurcate them and give it a shot.

Activities aligned with happiness:

- Various hobbies like sports, reading, gardening, etc.

- Quality time with family and loved ones

- Restful relaxation

- Engrossing and fulfilling work

- Contemplation and meditation

Activities considered hedonistic (mostly only in excess):

- Sex

- Gambling

- Drugs

- Gluttony

- Idleness

Immediately, we notice that most hedonistic activities can contribute to happiness if they’re partaken in moderation. I don’t believe many people would derive happiness from living the life of an ascetic monk, which takes pleasure to a deficient extreme. I contend that pleasures that would greatly interfere with the pursuit of other values would be considered “bad” and thus hedonistic, while those that either don’t or even promote other values would be considered “good.” For example:

- Excessive lust could lead to STDs and engaging in dangerous behaviors. Furthermore, making major relationship decisions on the basis thereof is a surefire way to derail any chances of a fulfilling love life.

- Gambling addictions bleed away one’s wealth and would naturally destroy marriages and any sort of financial goals.

- Drug addictions can cause so many problems, I hardly need to list them here.

- Gluttony is detrimental to physical, emotional, and mental health.

- Idleness can deflate one’s self-image and prevent self-fulfillment.

I would also point out that engaging in these activities would not be considered hedonistic if enjoyed in moderation and in the appropriate manner. There’s nothing harmful about sex with a romantic partner, playing a small-stakes poker game with friends, a drink or two at social occasions, enjoying a tasty meal, or taking a well-deserved break. Ultimately, hedonism is pleasures taken to an excessive extreme insofar as to sabotage other values.

Intent and Justification

Here, we will explore the second and more straightforward portion of the definition of will, one concerning the rationale behind the desired end. Allow me to illustrate the necessity of this qualifier with a simple example.

Suppose Kai is a teenager with stereotypical Asian tiger parents, the overbearing type who would do whatever it takes to ensure their children’s academic and/or professional success, often to the detriment of all else (happiness, mental health, social skills, etc.). Kai resents the strict measures his parents take, such as:

- Forcing Kai to play some instrument, not for enjoyment but purely to adorn his college applications

- Punishing even the most honest and harmless mistakes, thereby associating anything less than A- as failure

- Constantly comparing Kai’s academic achievements with those of his friends and those of the children of family friends

- Guilting Kai into studying hard

As a result, Kai is a straight-A student in high school, beloved by all his teachers. He manages to land a spot at an elite Ivy League college, and after graduating, he finds a well-paying job as a software engineer. One day in his 30’s, he reflects back on his life and feels grateful for all his parents have done to ensure his academic and thereby professional success, even if he didn’t appreciate it at the time, even if they went a bit far at times. Although he wishes they would’ve been a bit more lenient on the social side, he still understands that they were looking out for his best interest.

So, did teenage Kai follow his own will? He hadn’t believed in the desirability of academic success on the basis of a clear rationale linking said end to his value of professional success. Rather, he had very little choice in the matter. And thus, by our original definition of the will and by the absence of his own justification of his actions using his core values, he did not follow his will. That rationale component is a necessary condition for the will.

Let’s next consider Deep Blue, the famous chess-playing computer developed by IBM. It uses brute force to evaluate as many moves as possible, but cannot think the same way humans are. Deep Blue cannot decide that its priority should be, for instance, to control the center and thus conclude that the best way to do so is to move a knight to a certain space. Even if it has a will, to win the game, there’s no train of logic that flows from each successive move to victory. It has no will.

Suppose technology advanced to a stage where Deep Blue can recognize its goal and formulate a sound strategy backed by logical justification instead of brute forcing every possible combination, then Deep Blue has achieved true intelligence and can be said to possess a will. At that point, The Terminator might not be so far-fetched after all…

Conclusion:

We have thus defined a person’s will as a desired end that reflects his values and is justified thereby. One’s values are things that are prioritized over others, for example good health, career ambition, etc., where the CORE values are those that rank at the very top of that hierarchy, usually compatible with virtue, like happiness, honesty, justice, etc. Although it all sounds so simple, core values are subconscious, so most people aren’t even aware of what they value the most until it’s too late, when they wallow in regret in the twilight years. Was this all just a fancy way of confirming the age-old wisdom, that living to live a regretless life, you have to be true to yourself? Perhaps!