As Nietzsche discussed in his book, On the Genealogy of Morals, the good vs evil dichotomy (ethical dualism) originated with Zoroastrianism, further being spread with the advent and expansion of Christianity. He argues that this dualism inverts the natural and fundamental distinction between good vs bad. I largely agree with him, and in this post, I will reject this very dualism that has permeated conventional ethics today and the foundation of moral absolutism it requires. In other words, I will demonstrate the absurdity and futility of calling something “evil.”

Quick side note: I want to make it clear that I obviously don’t think people like Hitler or Stalin aren’t bad, but rather that there’s no point in calling them “evil,” which often can prove counterproductive in your efforts to oppose said “evil” people. Secondly, I want to stress that the cosmic “good” in “good vs evil” is not the same as the relative “good” in “good vs bad,” in the same way that “bad” differs from “evil.” The former dichotomy is inherently morally absolute, whereas the latter is morally relative.

Genesis of good vs evil:

I’ll keep it brief: Nietzsche essentially argues that before “good vs evil,” there was “good vs bad,” where good meant dominance, wealth, magnanimity, health, strength, etc., while bad signified weakness, sickness, powerlessness, impotence, fragility, poverty. Judaism and Christianity largely flipped that framework, such that the good in “good vs evil” now associates with certain traits like poverty, meekness, impotence, humility, obedience, servitude, etc., and evil is now represented by wealth, influence, power, strength, etc. Please note that, obviously, not every Judeo-Christian “good” is an inversion of a traditional “good,” nor every “evil” an inversion of a traditional “bad.”

Under Christianity at least, you are expected to prostrate before and put your total faith in God, and no matter what sort of pathetic condition you find yourself in, so long as you have lived according to His word, God will make things right. This is a firm repudiation of the worldly in favor of the supernatural/abstract. Consider The Sermon on the Mount, Matthew 5:3-11,

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted.

Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.

Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be satisfied.

Blessed are the merciful, for they shall receive mercy.

Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.

Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God.

Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are you when others revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account.

It could be said that under Christianity, one could find solace in the miserable state of one’s earthly existence, knowing that the wicked will be punished in the afterlife. Nietzsche called this “slave morality,” since it is effectively a coping mechanism for the downtrodden (e.g. slaves) to rationalize their sorry lot. After all, suffering in life would be offset by salvation in heaven, while those who oppressed them would find themselves eternally damned for their “evil” on earth. While misery, weakness, poverty, etc. aren’t intrinsically desirable from a Judeo-Christian perspective, they are considered manifestations of a man’s devotion and faith to God, not necessarily a failing of their character (e.g. the saint who swears a vow of poverty). This, too, could be argued to be a coping mechanism; “I’m not poor and powerless because I’m incapable – it’s because I am a good person and a devout follower of God! Those rich and powerful are only thus because of their unscrupulous, scheming ways!” In essence, impotence, weakness, poverty, sickliness, etc. have become a proxy for Christian virtue.

I want to stress the fact that I don’t have anything against Christianity in particular; my goal here is to point out and critique the Judeo-Christian ethics that have become such convention today, that anybody who questions them becomes a pariah. I believe that this inverted set of traditional values aren’t particularly persuasive in of themselves (there’s nothing intrinsically good about being poor, miserable, self-sacrifice), but that the vast majority of people choose to follow them for other benefits – social rewards, a sense of community, etc. I’m certain that the occasional saint is perfectly happy giving away his wealth to the poor even if there’s no camera to film him in the act or a press release to follow. However, that’s not true for most people. Why do corporations give some pittance to charity? For the good publicity, of course. Why do jihadis give up their life? For the promised land, of course, not because they enjoy killing themselves. In fact, the Hashashins (page 67) may have been some of the earliest Islamic terrorists, and they were convinced to carry out these suicidal tasks for the promised land.

To summarize, under the Judeo-Christian moral framework of good vs evil, while poverty, misery, wretchedness, meekness, sickliness, etc. aren’t considered virtues, these qualities are seen as proxies thereof. In the same way that wealth, power, influence, etc. are supposedly attained by unscrupulous means by secular, faithless people, poverty, weakness, impotence, etc. are signs of moral righteousness, spirituality, and faith. After all, if it takes a lack of virtue to seize power, then by extension, those who are virtuous must also be powerless (in the earthly realm).

On evil:

The most salient question follows, what exactly is “evil?” By the technical definition, it would be pretty much anything contrary to the commandments and values of God. In theory, religion provides a set of normative, universal values against which people and actions could be judged – the practitioners thereof must adhere to those values. If it is Godly and good to love your fellow man, to aid him, and to do no harm, then it must necessarily be ungodly and “evil” to do the opposite.

However, today, the word “evil” is almost always used outside the religious context, so that technical definition would not suffice. Moreover, I would argue that the word “evil” inherently implies a universal and absolute set of values, i.e. if something is considered “evil,” it cannot be considered “good” (under the same moral framework) by anybody else’s perspective. When you claim an action or a person is evil, you essentially take on an absolute judgment thereof, wherein further investigation/inquiry is preemptively deemed pointless. In fact, it’s the oldest political trick in the book to dodge scrutiny by branding anybody who doesn’t immediately swear eternal vengeance against a perceived evil as complicit in said evil.

I claim that calling someone or something “evil” today implies a number of things:

- It assumes there exists a set of higher (tantamount to “godly”), universal, absolute, timeless values that the overwhelming majority of people follow

- It implies that anyone who doesn’t subscribe to said values are of inferior moral value

- It claims said person/thing/action is so contrary to those values as to warrant such an adjective

- It suggests that no normal, decent person (especially the accuser) would do the same thing if he were in the position of the “evil” person

Refutation of moral absolutism, universality, and timelessness:

As mentioned above, the word “evil” inherently implies a set of absolute, universal, and timeless values. This means that not only does everybody adhere to these values since forever and also for eternity, but that there exist some principles that should never be violated no matter the outcome. Allow me to address those points one by one.

Timelessness:

Considering the popular conception of “evil,” if a person claims something is considered evil today, then that person believes it should still be considered evil 100 years from today by the usage of that term. Similarly, for something a person considers good or acceptable (in the good vs evil framework) today, that person wouldn’t expect it to suddenly become evil in 100 years. After all, nobody wants to be seen as an active participant to evil by future generations!

Timelessness of morality is perhaps the easiest to reject – it’s quite clear for anybody who studied history that what’s morally acceptable changes over time. Whereas it may seem completely absurd that slavery could be accepted by society, that was indeed the case for the vast majority of human history. To most people in most of history, enslaving those who lost a conflict was natural and obvious – only in the last few centuries did Europeans spearhead the abolition of this practice. We can easily dismiss the vast majority of human history as barbaric and uncivilized in a blatant expression of presentism, yet could you really claim that someone who’s against slavery today (vast majority of people living in liberal democracies) wouldn’t have been completely fine with slavery had they been born 400 years ago?

And then consider contraception and abortions, both of which most Western people considered evil not even a hundred or so years ago (Catholic Church still considers artificial contraception evil). Today, Western society at least has become much more accepting of both.

Furthermore, let’s look forward in the future and fully dispel any chronocentrism – how do we know that eating meat won’t be viewed in 50 years the same way slavery is viewed today? In other words, is it any fairer for us to call the average slave owner in 1600 “evil” than for someone living in 2070 to call the average omnivorous person today “evil”?

Universality:

Calling something “evil” implies that all should find that person/thing/action just as heinous as the accuser does. The word itself elicits a sense of universality and appeals to consensus. By that accusation, you appeal to a higher basis of judgment, which is supposedly abided by all. Whereas if you want to merely express your personal difference of opinion, you wouldn’t resort to the word “evil.”

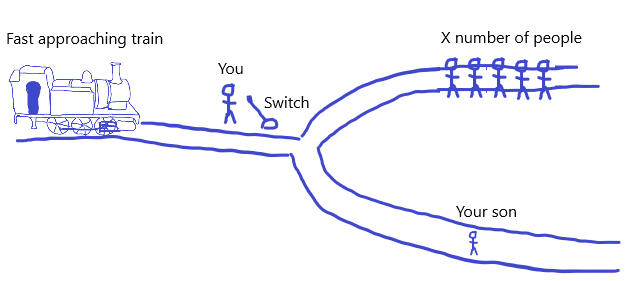

Consider the act of killing a person in isolation – the vast majority of people would consider that morally wrong. Let’s consider the classic trolley problem, where on one track, your child is tied to the rails, and on the only other track, 5 people are tied to the rails. A train is rapidly approaching, and you must decide which track the train takes and effectively who dies/who lives. To make this thought experiment more appropriate, instead of 5 people, let’s substitute it with X people – what is the highest number of people you’d be willing to sacrifice for your child’s life?

The universalist position claims that there’s one “correct” answer for this ethical dilemma for everybody, i.e. there’s some X that everybody would agree on. This is obviously false, since not everybody morally values even their own child the same, let alone the lives of strangers. Is it any less valid that a person chooses 10 or 1,000? Is a man any eviler for loving his child so dearly as being willing to sacrifice such a large number of strangers than the man willing to save even a few people with his child’s life? How do you figure that your 543 is more valid than someone else’s 28?

Is it important for a society to have a set of largely shared values? Absolutely. But let’s not pretend like everybody even within the same culture has the same exact set of values. Obviously, there will be some people or actions that pretty much everybody will agree are contrary to their values – there will be some arbitrarily large number for X, where almost everybody is willing to sacrifice their child for. Is the person with the largest X the “evil” person? If we either eliminate him or “deradicalize” him to reduce his X, wouldn’t that make the person with the next highest X the “evil” person? Where do we stop? And thus, we have circled back to the original question: where is the “correct” X?

What about serial killers, you may ask, those who kill for nothing but enjoyment? It’s not exactly interesting or fruitful to discuss fringe cases where literally everybody across time and space agrees. And what’s even the point of calling them “evil” for such specific cases, when it’s so obvious that everybody already agrees? Why not just call them murderous psychopaths incompatible with society? At least that has information content.

Absolutism:

Moral absolutism holds that there are actions intrinsically right or wrong in principle, regardless of circumstances, and thus would be always immoral. Almost always, calling a person/thing/action “evil” is a reductive act, whereby nuance and context are lost. It’s also frequently used as political rhetoric to create a strawman of the opponent’s position and then moralize the position.

Consider the merchant – a frequently reviled class throughout history and across geographies for their “profiteering” and not producing any tangible goods. Then consider one of the seven deadly sins: greed. No doubt many people throughout history considered merchants to be morally reprehensible for their greed and self-interest, even evil. Yet is greed (or the less dysphemistic term, self-interest) such an absolute sin as people make it out to be? Are we missing some nuance in labeling this “sin” as “evil”? As it turns out, anyone with even the most basic understanding of economics knows that self-interest drives the world. Moreover, is it so wrong to strive to provide the best one can for one’s family? Would anyone take on new ventures and new risks with the same audacity, the same drive, the same enthusiasm as he would for his own sake as opposed to the sake of some vague collective like “society”? After all, the merchant has risked a significant amount of his own capital and perhaps even his own life in transporting the goods from one place to another, supplying his customers with products they would not otherwise have had access. Why shouldn’t he be justly compensated?

In my opinion, and I believe the same goes for everyone, there are no such things as inviolable principles. At the risk of going beyond the scope of this post, I contend that all deontological ethics can be traced back to consequentialist ethics; in other words, even the strongest held principle will be trumped by some arbitrarily large cost of adhering to that principle. For example, consider innocent civilians – surely not harming innocent civilians is an inviolable principle? Yet, a very strong argument can be made that the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were justified from the American perspective. In that instance, the cost of adhering to the principle of not harming innocent civilians is the lives of several hundred thousand US troops (even if we assume not a single Japanese civilian would’ve been killed in an invasion scenario). Would you be willing to pay it as a cost of following your principles? Are you really the one paying the price if you have no actual risk of death?

To see how far this idea of absolutism has permeated our collective morality, consider how often popular media pounds the underlying moral of “protect the weak” into our minds by. Unfailingly, the good guy is always the person who risks life and limb to protect the defenseless and powerless – I’m sure you have subconsciously wondered, why? The act is so ingrained that nobody ever bothers to dig a little deeper and ask some questions. I understand that I’m going to sound like an ass to the average person, but I hope that the type of person who would read this far into my ramblings has the ability to entertain abstractions and challenges to their morality without becoming emotionally charged. Is there anything inherently virtuous about being weak that makes the weak so worthy of protection at the expense of the mighty? Is the rabbit praiseworthy in its peaceful nature purely on account of its inability to do harm? Is the “big bad wolf” evil by nature of its carnivorism?

The hypocrisy of those who cry “evil”

One of the funniest instances of someone crying “evil” was when Barry Diller ranted against Apple’s App Store charging exorbitant fees. I will admit that while Barry never used the word “evil,” he heavily implied it to be such. The sentiment was identical; he called the fees “disgusting” and “criminal” (it’s not actually a crime). Had he actually claimed the fees were evil, nothing would’ve changed.

Context: Barry Diller is a multi-billionaire who chairs both the boards of IAC and Expedia Group. Several of his companies’ apps, like Match.com, are distributed to iPhone users through the Apple App Store, which charges 30% commissions (now reduced to 15%) on every single dollar of transactions made through these apps. Barring the occasional jailbroken iPhone, all apps for iPhone must be downloaded through the App Store, ensuring that Apple has a monopoly over access to its own users.

Barry here depicts himself as the powerless, wronged victim and Apple as the big powerful evil oppressor. Is anyone actually fooled that ol’ Barry wouldn’t do the exact same thing if he were the CEO of Apple? It’s perfectly reasonable for Barry to hate Apple’s pricing strategy because it harms him financially, but does he have just cause to moralize? In fact, show me a single person crying “evil” about Apple’s pricing strategy who would honestly not do the same exact thing if they were leading Apple?

It’s very easy to bemoan how someone more powerful than you is exercising their power to offer you an arrangement you find “unfair” because you would’ve been able to get more concessions had you not been so weak. Yet the moment you attain the same power over someone else, you wouldn’t hesitate to wield that very power to obtain a similarly self-beneficial arrangement. Let’s be frank here – it takes an incredibly magnanimous person to not exploit their advantages for their own gain when they have the opportunity to do so! Just look at communists, the biggest losers and whiners on the planet – see how loudly they cry “oppression!” yet how quickly they turn around to oppress as soon as they seize control.

The view of the uninvolved observer

One of my favorite lines to use against those who frequently appeal to morality is, “it’s easy to moralize when you have nothing at stake.” Another frequent source of accusations of “evil” are those who merely observe situations where they are not involved. The accuser typically does not have a full grasp of the situation, context involved (stakes), nor the same information that the participants are privy to. Because if the accuser found himself in the same spot as the participants, he may very well resort to the very “evil” he accuses them of!

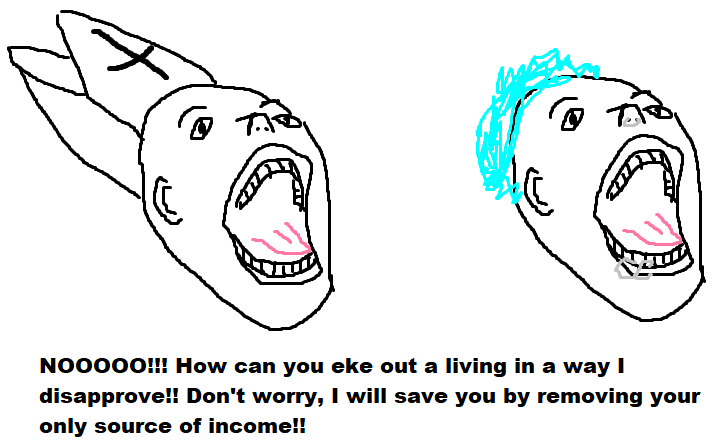

A great example thereof are moral crusades that used to be perpetrated by conservative, traditionalist factions, but is now led by moral purists on the left. I want to preface this by saying that I don’t think moral crusades are necessarily bad, especially since they can help facilitate positive long-term changes to society (e.g. abolitionism, environmentalism, women’s suffrage, etc.). However, moral crusades that are initiated to stamp out some perceived “evil” without truly understanding why some people engage in said “evil” can lead to some awful results. It’s also a lot easier to succeed when the person you’re trying to convince has similar values to you, i.e. it’s impossible for vegan who considers animals to have the same moral value as humans to convert someone who doesn’t.

Historically, the most infamous moral campaigns of outrage were typically waged against the conventional sins like alcohol, prostitution, pornography, smoking, drugs, etc. Today, moral crusades are waged against more nebulous concepts such as racism, sexism, xenophobia, etc. (though gun ownership is one that’s pretty concrete). Take the prohibition movement for example. It was effectively an attempt to forcibly impose the activists’ values on the rest of society (i.e. that drinking alcohol made you a lesser person) and was also founded on some faulty premises, that alcohol was the source of all social ills like poverty, crime, violence, etc. Imagine some insufferable self-righteous know-it-alls shutting down your favorite bar because they think they’re doing you a favor. They care little about the potential benefits of legalized alcohol, since most of these activists don’t drink or participate in the business anyways. People’s livelihoods destroyed, opportunities for social gatherings closed; it’s easy to moralize when you have nothing at stake.

There was also a crusade against prostitution and human sex trafficking in the early 2000’s, led by moralistic outrage from both the conservative Christian right and radical feminists. For the Christians, prostitution was a perversion of their values and thus considered evil, whereas for the feminists, prostitution represented male domination, exploitation, and violence against women, which they obviously also saw as an evil. According to the article I linked above, the radical feminist organization Coalition Against Trafficking in Women claimed that “all prostitution exploits women, regardless of the women’s consent.” Ironically, while these two groups conflict on nearly all other issues, they allied on this and also did back in the 1980s against pornography.

These two groups presumably neither used the services of prostitutes nor engaged in the business of prostitution, so they are, by definition, uninvolved observers. I’m not suggesting that you shouldn’t intervene if you see something you consider wrong, but that the act of moralizing (i.e. calling said act “evil”) will eliminate all empathy with the parties actually involved. Perhaps some women find themselves in awful situations, where turning to prostitution is their only way of making a living for themselves and possibly their children. If you take away their source of income out of some moral outrage and dubious, sanctimonious claims (for supposedly their benefit) and without providing any viable alternatives, you won’t win any favors for “saving” these supposed “victims.” Better yet, would those same Christians and radical feminists not do the same if they find themselves in a similarly desperate situation instead of living in their middle or upper-middle class comfort?

What’s even more hilarious is that the real aim was to eliminate prostitution, while hiding behind the veneer of “combating human trafficking.” These activists successfully integrated their agenda into US policymaking, based on fallacious facts and statistics compiled by these moral busybodies. Many of the commonly cited figures designed to be sound vaguely true but provocative are completely bogus. I highly recommend you to read the article I’ve linked above.

Moralizing in policy

Now that I’ve presented my argument on why “good vs evil” is a ridiculous dichotomy founded on highly flawed presumptions, I will demonstrate why calling something/someone “evil” (the act of moralizing) can be detrimental from a practical perspective. While it may seem odd that something so theoretical could be so important, the moral framework one uses to determine policy can have far-reaching, enduring repercussions.

Recall 9/11 – a devastating attacks on American soil that killed almost 3,000 people. Understandably, the American people rallied and demanded the government, especially President Bush, to take decisive, retributive action against the people who orchestrated the attacks. And that, he did – Bush created a clear divide between terrorists and those who opposed terrorists. Famously, he stated, “you are either with us, or with the terrorists,” a clear declaration of a moral crusade on the evil of terrorism as the nation was whipped into a frenzy. As characteristic of any moral crusade, there was a clear delineation between the “good guys” and the “bad guys.” Make no mistake, this immediately became a holy war, where the just fought the unjust, the morally righteous against the despicable sinners. “It’s a war against evil people who conduct crimes against innocent people,” Bush said.

Where did it all go wrong in Afghanistan? “We will make no distinction between terrorists who committed these acts and those who harbor them.” Righteous fury burns like a wildfire – scorching everything indiscriminately.

Context: Al Qaeda was the group that planned and executed the 9/11 attacks, founded by Osama bin Laden, a Saudi. This was an entirely distinct group from the Taliban, who controlled Afghanistan in 2001 (they are also a fundamentalist Islamist group). In fact, many of the Taliban senior leadership opposed harboring al Qaeda, who were attacking foreign powers left and right, attracting unwanted international ire, whereas the Taliban held no international ambitions aside perhaps with the Pakistani Pashtun.

As a quick overview of Afghanistan’s tumultuous recent history, they had a pro-western, secular leadership until a general overthrew the monarchy in the 1973 coup. Then, there was the Saur Revolution, which saw the establishment of the Soviet-backed communist regime in 1978, sparking a series of conflicts that includes the Soviet-Afghan War, when the Soviets realized they had to intervene to stabilize the communist rule there. The Mujahedeen was a loose confederation of various tribes and ethnicities backed by the CIA that fought against the Soviet-backed communist regime.

After the Cold War ended and both the US and USSR agreed to cease all support for their respective proxies, Afghanistan was left with a power vacuum, where many warlords suddenly had to monetarily support their troops without the backing of the US. What did they have? A lot of weapons. Naturally, these Mujahedeen turned their guns against each other in a prolonged period of conflict and warlordism. It was an extraordinarily tough time for the Afghan people – people were slaughtered along ethnic lines, women raped frequently, people robbed in broad daylight by bandits/soldiers of the warlords (hard to tell the difference).

From the southern, rural region of Afghanistan, ethnic Pashtuns formed the Taliban, which consolidated power and pushed out most of the other warring factions, barring a couple of holdouts in north (the Northern Alliance). As of 2001, Taliban effectively controlled most of the country, imposing harsh Sharia law upon even the more liberalized cities. For better or worse, there was some semblance of stability, but the Taliban were no better than any other warlord in the way they massacred certain ethnic groups. However, it’s not absurd that many people, especially those living in the rural regions, would prefer life under Taliban rule vs the constant warlordism that ravaged the land before the Taliban.

The supreme leader of the Taliban Mullah Omar was friendly with bin Laden due to the latter’s aid during Soviet-Afghan war, so he refused to hand over Osama bin Laden to the US. They offered to extradite him to a neutral Muslim state and be tried in a Muslim court, provided the US give them evidence of bin Laden’s involvement in the 9/11 attacks, which Bush refused. The US gave the ultimatum – give us bin Laden unconditionally, or else. Note that many Taliban senior leaders did not want to antagonize the US and hated the fact that they were harboring these Arabs (al Qaeda), who pissed off foreigners; they wanted to just give up bin Laden, since they have enough problems domestically. Imagine if your “friend” provoked a bunch of thugs and hid in your house.

We went into Afghanistan with guns blazing, zealously hunting down the Taliban wherever we could find them. Even though their only wrongdoing was refusing to extradite a criminal, the way our righteous fury shifted to the Taliban was shocking – these were not the people who attacked us! The most hilarious development was that bin Laden fled to Pakistan shortly after the invasion began. Yet our crusade against the Taliban continued; we had evil to eradicate, after all.

What was initially supposed to be a war to capture the person responsible for an attack on the US turned into a two-decade long quagmire. As typical of bureaucratic mission creep, our goal morphed into establishing a liberal democracy in Afghanistan in a half-assed way, while pretending we’re letting the Afghan people rule themselves. In fact, the powers vested in the Afghan president was comparable to that of Afghan kings.

Oh, we did let the Afghan people rule Afghanistan – just certain Afghan warlords in particular. See, since we have defined this conflict as good vs evil, there had to be the good guys (us) and the bad guys (the Taliban and al Qaeda). Anybody who was against the bad guys were automatically good guys; there’s no place for nuance here – that’s the nature of dualism. And so, we began backing everybody who ever had the slightest grievance against the Taliban, even if (especially if) they were one of the brutal warlords who ravaged, raped, and robbed the people before the Taliban regime. My point isn’t that the Taliban isn’t bad; it’s that the Taliban wasn’t singularly bad, yet calling them “evil” and putting them on the same level as terrorists made it that way. They were not significantly better or worse than those so-called US “allies,” and most definitely not as bad as al Qaeda.

Without diving too deeply into why we failed, which itself deserves a full post, let’s examine what the consequences of our philosophy and mindset going into the invasion. Because we are the good guys (“good” from “good vs evil”), we cannot do a full occupation like we did in Japan post-WWII (also because of the concurrent Iraq War); that was simply not politically or diplomatically feasible. Thus, we had to rely on proxies to do a lot of our fighting and intel gathering for us. These proxies were picked merely by their animosity to the Taliban – if you hate the Taliban, you received US support. This meant that:

- Political leaders answered to the US rather than the people, despite elections (elections were a complete sham, filled to the brim with fraud). Just look at President Karzai, the first president under the US-backed regime.

- Local contractors and officials got unbelievably wealthy off of business with the US military, though they were hardly better than warlords, except now institutionally backed.

- Sometimes, security contractors would simply bribe the Taliban not to attack the convoys they “protect”!

- US “allies” fed false intel to the US military, siccing them to attack their personal enemies, who were branded as Taliban, al Qaeda, or Taliban/al Qaeda sympathizers, many of who were even US supporters! Of the 770 individuals incarcerated at Guantanamo, the US govt only charged 23 with war crimes as of Oct 2008. We were in a righteous crusade! It didn’t matter if a couple of eggs were broken to make the omelet.

- It got so brutal that some people were repeatedly detained and tortured due to having offended some US “ally” somehow, requiring their families to bribe for their release each time, a complete extortion racket.

- Anybody who spoke out against this arrangement found themselves victims of this exact treatment.

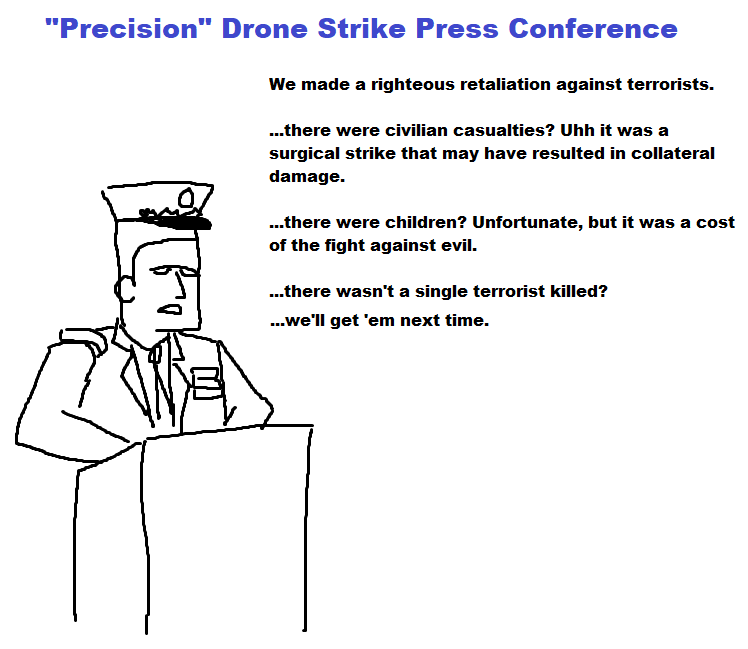

- Drone strikes, despite all the claims of precision, didn’t do much when the target was wrong to begin with.

- US never held their own “allies” accountable for their atrocities, especially when the US was complicit in them. We were on the same side, the good guys’ side, after all.

- US-backed Northern Alliance massacred up to 2,000 Taliban prisoners captured or had surrendered.

- When some Taliban offered to surrender to President Karzai, a US-backed warlord had them imprisoned and tortured by the NDS, an intelligence agency created by the CIA.

- US-backed strongmen would secretly capture and torture tribal rivals, civilians, etc.

- The US saw the Taliban’s conservative Islamic policies (basically the principles of Sharia law) as “evil” and thus attempted to force Western liberalism on Afghanistan. However, Taliban agenda was a reflection of traditional rural Afghan culture, not some exogenous faction forcibly imposing Sharia law on the people. If you’re going to kill everybody in Afghanistan who didn’t support women getting education, going outside by themselves, etc., you might as well kill most of the rural population in addition to the Taliban themselves.

How did we justify subjecting Taliban and supposed Taliban to these atrocities? The way Dick Cheney justified Guantanamo Bay exemplifies the way we framed this conflict into a moral one. “These are evil people,” he said of Guantanamo Bay prisoners, “and we’re not going to win this fight by turning the other cheek.” Not only did our righteous fury burn the Afghan people, it also burned ourselves in the amount of time, money, resources, reputation, lives, etc. this entire two-decade conflict cost. In fact, because of the pain and injustices inflicted on the Afghan people and the sheer corruption by the US-backed regime, the Taliban drew support from disillusioned Afghans, which led to their revival and resurgence.

So morbidly poetic the way we left Afghanistan that it was clear we learned nothing from this entire debacle. As we finally withdrew from Afghanistan, ISIS, a sworn enemy of ours and the Taliban’s, set off two bombs outside the crowded Kabul airport, where many people were hoping to evacuate from. 13 US troops were killed in the explosion, along with 169 Afghan civilians. In an act of “righteous” retribution, we launched a drone strike in Kabul that supposedly prevented an imminent attack on US forces, yet it turns out all it did was kill ten civilians, including seven children. The so-called militant hauling explosives in his car was an aid worker for Nutrition and Education International (a US-based humanitarian organization), moving water.

Consequences of moralizing

With all of that said, let’s review the reasons why moralizing people, things, and actions is a bad idea:

- Inability to empathize – righteous fury blinds us to the context and stakes involved for the relevant parties

- Erases nuance – moralizing is an inherently reductive exercise, whereby the contrast slider is turned all the way up, resulting the replacement of all shades of grey with either black or white

- Preempts discussion – as a result of the polarizing nature of the act of moralizing, you’re placed into either one camp or another. There can be no hesitation or constructive critique of one’s own side, lest one be labeled as an enemy.

- Self-destruction – not only could righteous fury scorch bystanders, it can also inflict burns on yourself. You begin to lose sight of your original objective, instead, focusing on zealously righting some perceived wrong be it through vengeance or otherwise.

The alternative to “good vs evil”

I would be remiss if I didn’t provide some alternative to “good vs evil;” I believe the aforementioned “good vs bad” dichotomy to be preferable. The key difference here is that “good vs bad” is a relative moral framework rather than the timeless, universal, and absolute framework presumed by “good vs evil.” In other words, when I call something “bad,” I’m only claiming that the person/action/thing is contrary to my personal values, without any commentary on how it would/should be judged by society’s morality. I would implicitly acknowledge that my set of personal values may not apply universally and that others can view the situation different than I do.

Often, a moral judgment is unnecessary – instead of saying that the Taliban is “evil” and hates our way of life and wants to destroy democracy, it’s far more productive to say that the Taliban’s agenda reflects centuries of social norms and traditions of rural Afghans, and they were themselves a response to the brutal warlordism after the Soviet-Afghan War. Sure, the latter is a mouthful, but it actually has actionable information content.

And for completely uncontroversial people like the Nazis or the Soviets – why even bother calling them “evil” in the first place? Merely calling them “evil” tells us nothing of their actual underlying motivations for doing what they do, but rather reduces them to a caricature of some evil villain hell-bent on sowing destruction purely for the sake of destruction. While there exist certain people who can, for practical purposes, be characterized as such villains (ISIS, serial killers, etc.), we should still refrain from reducing a conflict into black and white, since doing so can cause us to ally with the wrong people. In the case of Hitler vs Stalin – was it really the right move to surrender eastern Germany and Eastern Europe to the Soviets? Should such a decision to ally with them been so easily made in the face of fascist aggression? I don’t have the answers to those and am aware of potential hindsight bias, but I think it’s important to determine if our ally’s values or our enemy’s values are more discordant with our own. We should also keep in mind that if the average person today lived in Germany during the rise of the Nazis, they would’ve likely joined the Nazis too.

Repudiation of dualism

Whether or not Nietzsche’s psychoanalysis of the origin of dualism was correct, it matters little. What’s clear to me is that reducing complex motivations of people into a simple “good vs evil” dichotomy benefits no one except the opportunists who use it as a tool to manipulate others. Under the false assumption of some timeless, universal, and absolute set of values, calling something “evil” bears no information content except an exhortation of said “evil’s” total eradication. Using the word implies cosmic judgment upon some sinner or sin, whereby the accuser presumes the guilt of the accused. Many moral crusades have been waged against these perceived “evils,” and many of them inflicted significant collateral damage, often resulting in adverse consequences that outweigh the intended benefits from the campaign’s success (e.g. prohibition). Join me by eliminating the word “evil” from your vocabulary, and if not, at least take a closer examination of what exactly you mean the next time you or someone else calls something “evil.”