Know thyself. We hear that trite line frequently uttered as if something profound. Like many proverbs and famous quotes, people tend to overuse that phrase until they’ve stripped it of the original meaning. The goal here is to dissect this truism to see just what knowing oneself entails.

Recall that confidence and self-respect are consequences of pride, which I’ve defined in a prior post as setting and meeting high standards for oneself. Why is this? It’s because one’s thoughts and actions are inextricably linked to knowledge of oneself. When one acts virtuously, self-image improves.

As usual, we being with a few main axioms and go from there.

- At birth a man has no knowledge of himself and must discover who he is over time (as clichéd as that sounds)

- Every single action and thought colors one’s self-image, so long as memories thereof linger

- Humility (acknowledgement of the fallibility of man and self) is the only cure for past shame (failing to set or meet high standards) – I’m aware of how Christian this sounds

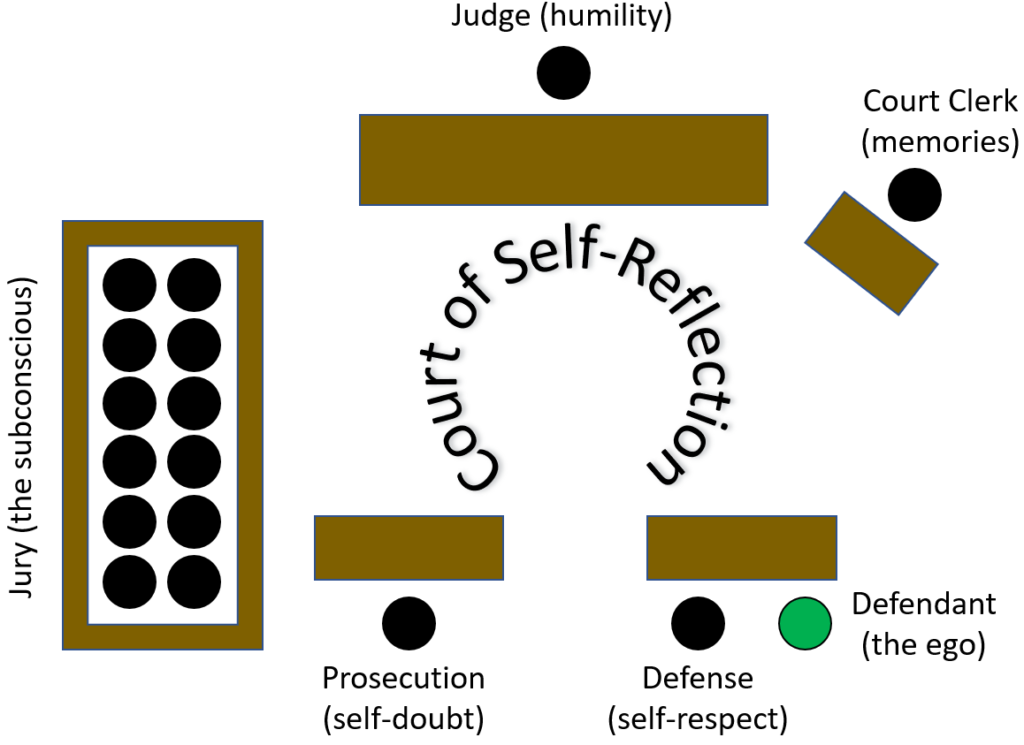

With that, I will introduce an analogy for understanding self-image: the court of self-reflection.

The defendant – the ego

The average person loves to judge strangers, especially those who stand above him in the social or economic hierarchy. He especially revels in every opportunity to feel morally superior when public figures make honest mistakes or otherwise err like any human occasionally would. These days, it almost feels like the Cultural Revolution once again, when neighbors turn on each other over the most trivial “sins” and oust one another to a cheering mob.

However, in the Court of Self-Reflection, the defendant on trial is the self. The jury (one’s own subconscious) will pass judgment on the defendant by examining evidence submitted by the prosecution and the defense. In this court, there is no final verdict, but rather the jury delivers continuous judgment based on past evidence as well as new evidence as it comes in.

The prosecution – self-doubt and the defense – self-respect

Whereas the prosecution attempts to bring out all the terrible or shameful things one has done/thought/spoken as well as interpret them in the most negative light, the defense presents all the great and respectable things, displayed in the best angle. A prosecution armed with compelling evidence can topple one’s self-esteem the same way a robust defense can build up one’s confidence. A draconian prosecution results in crippling insecurity, while an overzealous defense leads to blinding overconfidence.

As it relates to pride and shame that I’ve previously defined, the prosecution will present examples of shame to the court, while the defense will present instances of pride.

The verdict – self-image

As the jury reviews evidence and arguments from the prosecution and the defense, it passes ongoing judgments of the self. Every new action and thought by the defendant are scrutinized and incorporated into that verdict. So long as one remembers the train of thought behind each action and the results of one’s actions, they can and will be submitted to the court, similar to what the Miranda rights warns – “anything you say (or do) can and will be used against you in” the Court of Self-Reflection. Here are some examples of what the verdict could read:

- “John Doe has cheated on his wife and lies to his daughter frequently. The jury finds that he is a terrible husband and father,”

- “Bob Smith spends all his free time outside of work playing video games and smoking marijuana. The jury finds that he is an ambitionless, complacent loafer.”

- “Maria Brown has worked tirelessly in pursuit of and successfully attained her lifelong dream of opening a bakery. The jury finds that she is driven and diligent woman worthy of success.”

The jury – the subconscious

In the Court of Self-Reflection, the subconscious is the jury that passes judgment on the defendant. A person has no control over his subconscious, as the prefix of that word implies – one has no influence over one’s self-image. A person can rationalize all he wants regarding a past action or thought, but the mental gymnastics of the conscious can never deceive the subconscious. “I stole the money from the cash register because it belongs to an evil corporation that exploits its workers, not because I’m an amoral opportunist!” Unfortunately, the subconscious will never buy such a flimsy lie.

Despite its immunity to willful self-deception, the jury of the Court of Reflection surprisingly mimics real life juries in their bias and often flawed judgment. Like its host, the subconscious of a human being can easily succumb to confirmation bias and can get petty and vengeful when the prosecution carries (insecurity) or exuberant and uncritical when the defense dominates (overconfidence).

- Once the subconscious has internalized a heavily negative self-image, all further evidence will be viewed with a negative slant. If the jury has already decided that the defendant is guilty, then confirmation bias kicks in, and suddenly, verdicts become, “Joe Schmoe is a terribly selfish person, so this one time he volunteers at the soup kitchen is really for social media fame rather than altruism.” It is difficult to consciously extricate oneself after one has fallen into the whirlpool of self-doubt.

- If the jury has already acquitted the defendant, when confirmation bias kicks in, verdicts could become, “James Adams is a brilliant, hardworking man, so he’s doing his future employer a service by lying during the interview, since HR asks such pointless, irrelevant questions.” Although that may seem like intentional self-deception, the overconfident has internalized the believe in their own infallibility, meaning that their subconscious does the mental gymnastics for them.

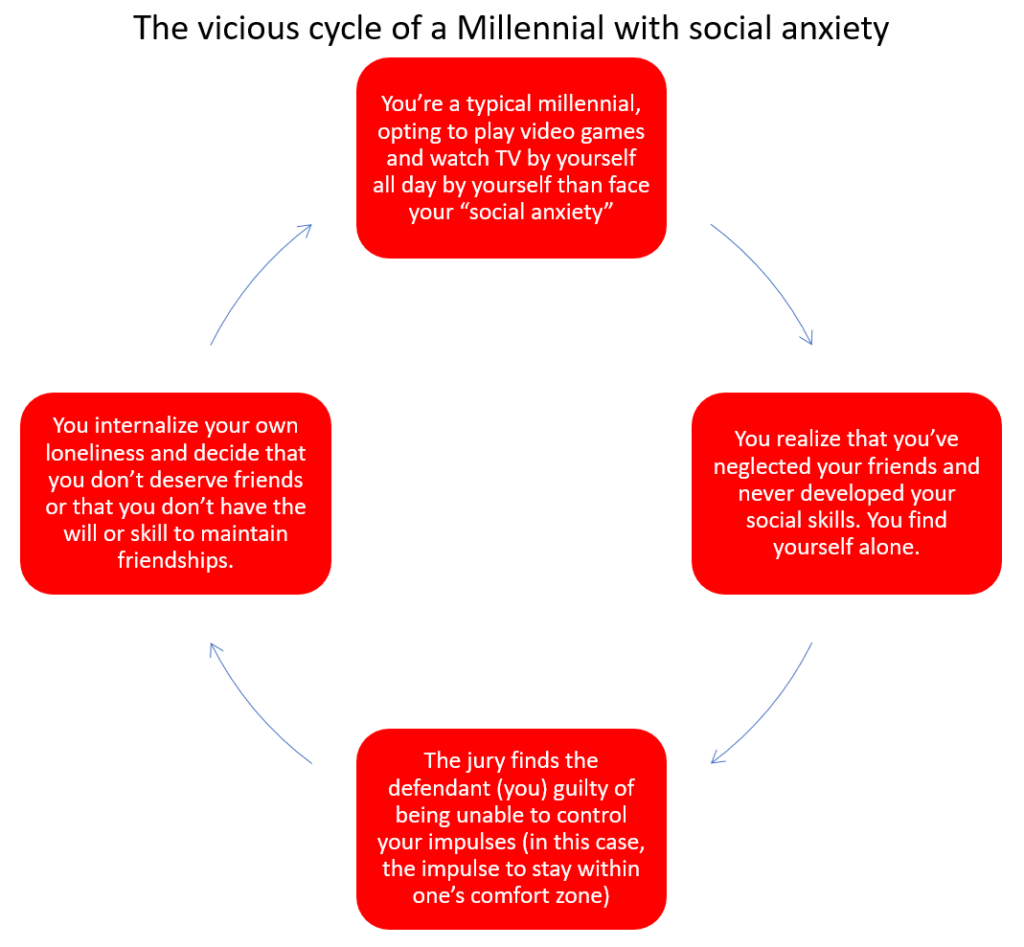

When the prosecution dominates, the jury can become ruthless. This results in a vicious cycle of self-hatred, where low self-esteem reduces motivation to do better, which then reinforces low self-esteem. I suspect that this is a major contributor to the epidemic of depression and anxiety in today’s youth.

The judge – humility

Unlike in a real court, the Court of Self-Reflection requires no judge. And without a judge, there is no law and order in the courtroom, no legal protections for the defendant. Without a judge, the legal system becomes indistinguishable from mob justice, an oxymoron. Just like in real life, the judge in the Court of Self-Reflection shall temper the passions of the jury and also dictate the admissibility of evidence. And that role falls onto humility.

As I have established previously, the jury (the subconscious) can be temperamental and biased. If left entirely to its own devices, the jury could cause one’s self-image to diverge wildly from reality. The presence of humility, however, shields he defendant against a potentially vindictive, unruly mob jury – it is not only the antidote to overconfidence, but it can also help the insecure overcome their past sins and shame, thereby slowly curing said insecurity.

Humility being diametrically opposed to overconfidence should be self-evident and requires no elaboration. At the risk of sounding incredibly Christian, I will instead demonstrate how humility can help the meek and shameful move on. I’m forever an atheist, for what it’s worth.

First, recall all the times you’ve spent lying awake in bed, your thoughts tormenting you with shameful memories. Perhaps you’ve done regrettable things in your youth that you’re not proud of. Perhaps it has haunted you over the years and brought about many sleepless nights. That would be when the prosecution found a particularly juicy piece of evidence to use against your ego – so strong, in fact, that the jury (your subconscious) frequently references the events, years later. I don’t remember much about my early childhood, but I do vividly remember:

- That time I got a pet chicken and I accidentally stepped on it when chasing it around, Lennie style

- That time I stole $20 out of grandma’s purse to buy a new toy

- That time I purposely ran into a dead end during tag, when a girl I liked was “it”

That’s where the judge, humility, comes in. Recall that in a real court, the judge reviews evidence and determines admissibility. Shoddy, unreliable evidence would be disallowed from court, as well as irrelevant prior convictions. Most importantly, the judge can rule that a prior conviction has no bearing on the current verdict. Just as a petty theft conviction 15 years ago is unrelated to a trial on charge of armed robbery, something shameful one has done a decade ago should not color one’s self-image today, especially if one has changed over the years.

Humility, the acknowledgement of one’s own fallibility and shortcomings, allows one to forgive oneself for past shame and to move forward. Humility permits one to think, “I’m nearly 30, and I’ve been coasting through life without direction out of a fear of failure. However, I forgive my past self and recognize my flaws – it’s not too late to pursue my dreams. I may very well fail, but trying and failing certainly beats sitting around wallowing in self-pity.” Instead of the jury (subconscious) pummeling the defendant (ego) into the ground in a vengeful wrath after being riled up by the abundant evidence presented by the prosecution, the judge (humility) intervenes and removes irrelevant past shames from being admitted for consideration. While those past shames will likely never be forgotten, those sleepless nights become few and far between.

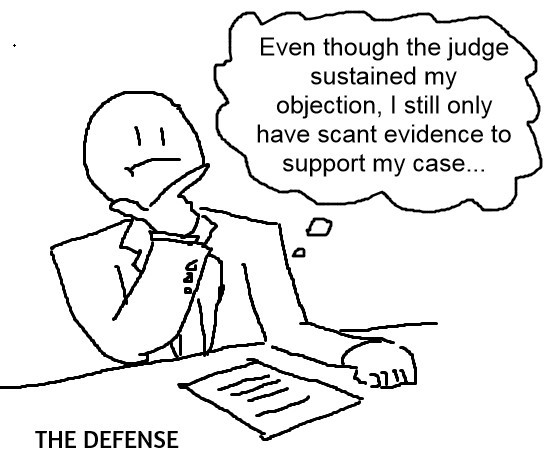

As a caveat, we should remember that even the judge cannot save the ego from a weak defense. In other words, humility will not help if the defense has little evidence. Yes, the judge might disallow the most absurd arguments from the prosecution, but if the defense has no legs to stand on even during a fair trial, then the verdict is a foregone conclusion. Therefore, there has to be some pride and confidence hidden within a person for humility to moderate one’s self-doubts – the defense’s case needs to have some merit!

How does this analogy differ from self-help?

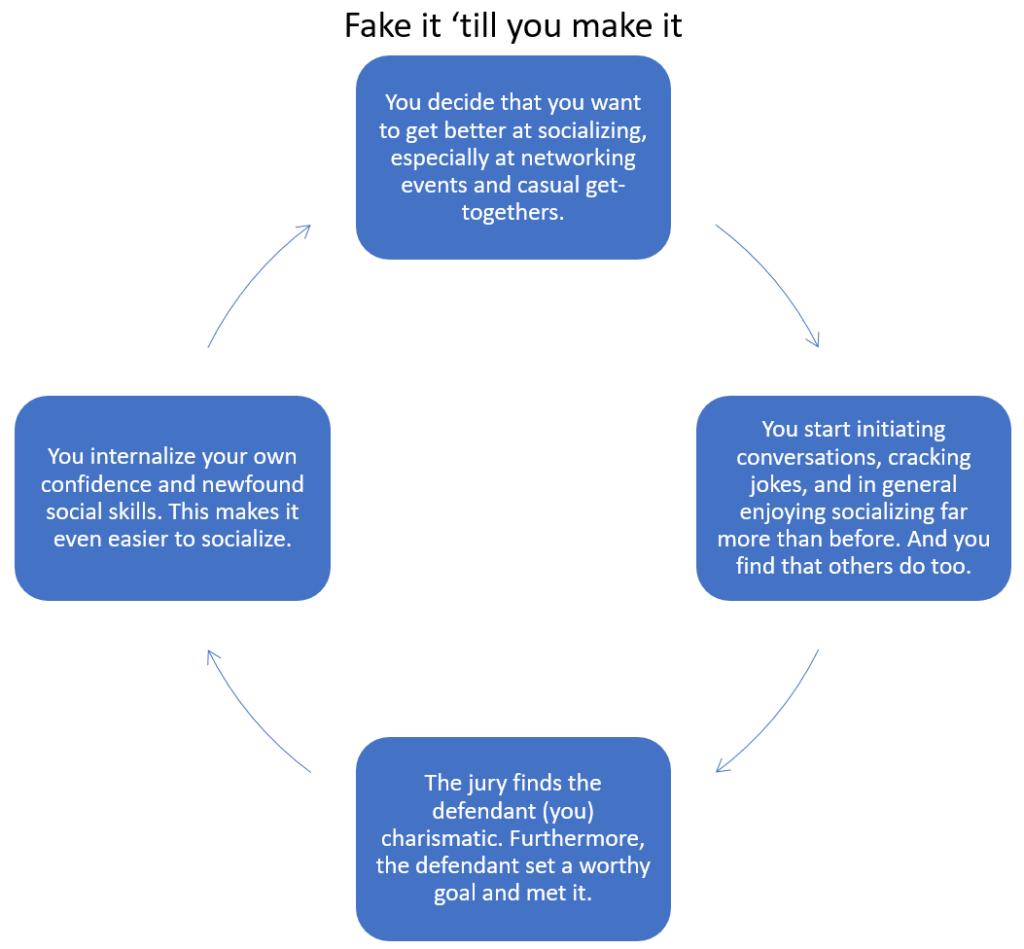

Now that we have created a robust analogy for self-image, what does it all mean? What conclusions can we draw? Unlike self-help books that try to treat the symptoms rather than the disease, my goal here is to reveal the root causes and mechanisms of the disease. I offer an explanation of WHY a person feels self-loathing or self-respect and a model to understand how future actions/thoughts can impact that self-image.

Self-help books regularly advise people to “simply stop caring about other people’s opinions,” but that ignores the fact that seeking validation in the opinions of others is wholly subconscious. A person cannot just will themselves to stop caring about how others view them. That advice ignores the underlying cause – low self-esteem. Sure, you can tell the person, “nobody thinks about you that much at all; you’re too self-conscious.” But telling them that other people don’t care hasn’t solved their desire for confidence. They’ll still look for their self-worth exogenously, a pointless endeavor.

Despite what some self-help “gurus” suggest, just telling oneself “you’re worth it” will not sway the jury – recall that the conscious cannot directly influence the verdict in the Court of Self-Reflection. Self-image is subconscious. The only way to do it consciously is indirectly through providing compelling evidence. Again, one cannot will themselves into confidence any more than one can will themselves into happiness.

Examples of how evidence feeds the verdict:

Oftentimes, the prosecution can draw conclusions from actions that are seemingly innocuous, especially when those actions add up over time. Those conclusions may not be immediately obvious to the conscious, but one can be assured that there’s always a hidden implication or underlying cause to one’s decisions. There’s also a self-reinforcing effect, where taking certain actions increasingly internalizes the implications of those actions, leading to taking those actions more frequently. Remember, every decision reflects on your priorities and your principles – how much are they worth? Allow me to provide a couple of examples.

Suppose you made plans with friends to go out for dinner and then hit the city. However, 1 hour before the appointed time, you decide you’re just not feeling it; perhaps social anxiety kicks in or perhaps you’re feeling lazy and decide that watching Netflix is preferable. So, you decide to back out last minute with some excuse.

What kind of conclusions does the prosecution draw from this evidence?

- Your word is worthless and unreliable. Otherwise, you would honor your prior commitments unless some truly extenuating circumstances arise. If your word is broken on a whim, then it is worthless.

- You do not respect your friends’ time. If you did, you would not have abandoned them without advanced notice, possibly ruining their plans if your presence was critical to them having a good time.

- You let something as trifling as social anxiety prevent you from having a good time with your friends.

Perhaps your friends believe your lie/excuse, but your subconscious does not. Perhaps doing this once is not such a big deal, but when you do it repeatedly, those aforementioned conclusions start becoming internalized. “Perhaps my word is worth nothing. Perhaps I do not deserve my friends,” you might think.

Thoughts, not just actions, are also admissible evidence in the Court of Self-Reflection. Suppose you are pondering the professional achievements of a friend whom you consider more successful than you. Suppose, then, that you try to rationalize your relative inferiority by citing all the disadvantages you had comparatively, including being born into a lower-middle class family, having gone to a public college instead of a private one, not having professional connections, etc.

What kind of conclusions does the prosecution draw from this evidence?

- Whenever someone attributes the outcomes in their life to something other than themselves, they are in effect conceding their lack of agency, and it’s no different here. In other words, this line of thinking denies one’s self-determination. To protect the ego, people like to attribute their failures to extenuating circumstances and their successes to their own merits. You can’t have it both ways – accept that either you’re a mere leaf blowing in the winds of life or you’re a soaring eagle finding its own way.

- You are a petty person, prone to jealousy of your own friends. Otherwise, you would not be bothered by your friend’s success but should be happy instead.

- You are insecure about your professional life since you derive self-worth from it. Otherwise, you would not try to rationalize that discrepancy in professional performance.

At this point, it would be the judge’s (humility) role to intervene by disallowing said evidence from court by citing the following principles:

- Everyone has dark thoughts from time to time; there are no perfect saints. We should not allow these uncontrollable thoughts define the defendant.

- It’s pointless trying to compare oneself with others; it is far more productive to compare the present self with the past self.

- Even so, there’s nothing wrong with admitting that someone else surpasses oneself in certain areas. There’s no shame in recognizing one’s own fallibility.

Let’s look at a more positive example. Suppose you made a big mistake at work that cost your employer a bunch of money. Let’s also say that you could’ve had the opportunity to quietly shift the blame elsewhere, with no possibility of ever being found out – a risk-free proposition, with the only cost being on your conscience. Suppose you decide to admit your mistake and accept responsibility for cleaning up your own mess.

Notice how I did not say what happened afterwards, because the outcome doesn’t really matter, only the actions and underlying motivations. What kind of conclusions does the defense draw from this evidence?

- You are a principled man whose belief in higher ideals supersede his own self-interest.

- You refuse to let the fear of being fired sway you from your principles – that thought is empowering. Whereas a weak will bends to the lightest breeze, a powerful will withstands hurricanes.

- By accepting responsibility, you are reaffirming your own power to control your destiny, whereas a lesser man cannot.

Conclusion:

With that, I hope I’ve created a useful model for understanding how a person comes to perceive himself, how self-image is derived. With that knowledge, we can understand how to consciously improve our self-image in an organic way – by doing things that you consider admirable, even when nobody is around to commend you, for the person whose opinion OF you is most important IS you. It also helps to embrace humility, since a court without a judge is just mob justice. Thus, I’ve just outlined how pride/shame and arrogance/humility plays into the scale of confidence/insecurity. So, how does one become confident? The long and short of it is to follow a slightly modified version of the Christian “WWJD?” – “what would someone respectable do?”