In this article, I will attempt to convince you that pride and humility are neither antonyms nor related in the slightest. First, I will discuss the background on the virtues and then define the two terms.

Historical context of pride and humility:

Most virtues are universally understood to be admirable human qualities, insofar as being nearly self-evident. However, that’s not to say that there’s universal consensus on a single set of virtues – in certain instances, something considered a virtue in one culture could be seen as a vice in another. Consider pride and humility.

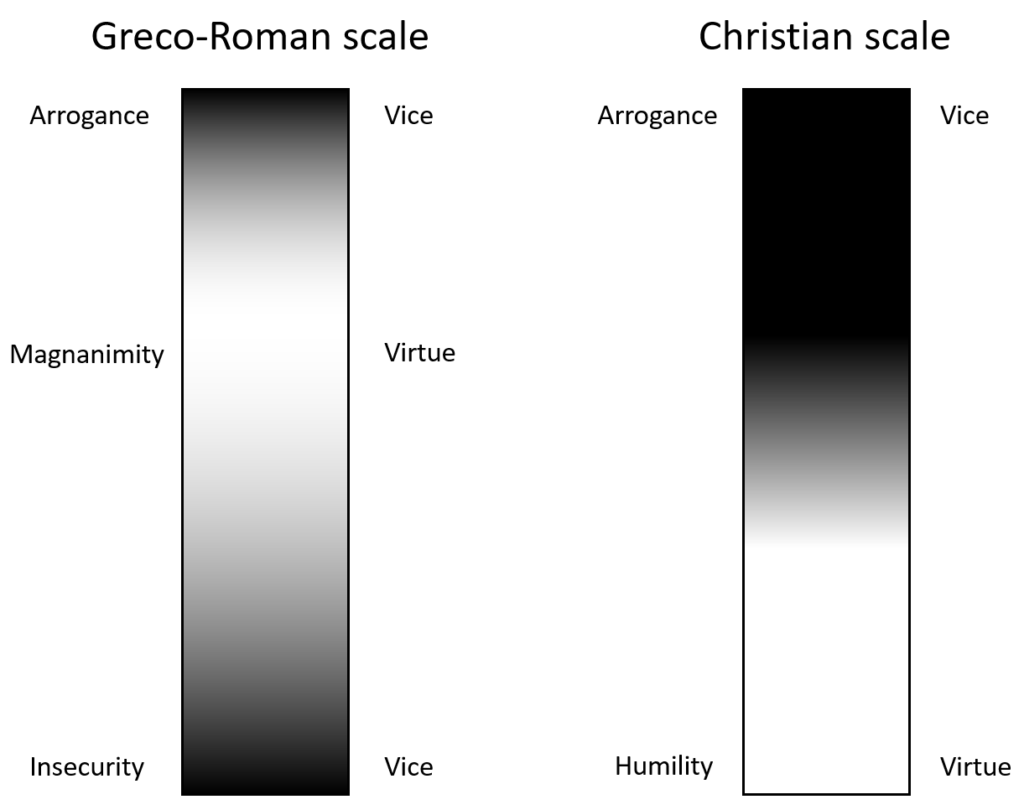

In Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle posits that virtues sit at the “golden mean” between the two extremes of vices (see chart below). For instance, courage is the happy medium between cowardice (deficiency of courage) and recklessness (excess of courage). As is reflective of Greco-Roman worldview, Aristotle deems pride, aka magnanimity, as a virtue – defined as believing oneself to be worthy of great things, with neither meekness nor vanity. At the deficient extreme, we have “smallness of soul,” which is associated with insecurity and low self-esteem, and at the opposite end, we have excess confidence, or vanity, arrogance, hubris, etc. Note the absence of humility; in fact, it’s debatable whether or not Aristotle even considers humility a virtue!

In contrast, Christianity considers virtues and vices to be a dichotomy, where the seven heavenly virtues diametrically oppose the seven deadly sins. We are most interested in the relationship between the sin of pride and the virtue of humility, for the purposes of this discussion. The Bible states, “blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted. Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth.” (Matthew 5). Christians believe that Jesus Christ’s submission to torture and execution at the hands of the Romans was commendable in its humility. That said, no serious follower of Christ would actually suggest that the Bible encourages people to be sycophantic grovelers. However, magnanimity isn’t considered a virtue under Christianity.

A virtuous man under Greco-Roman morality would surely be considered vain under Christianity, while a virtuous man under Christian morality would be seen as meek to his counterpart. I reject these two scales and propose a different interpretation – I don’t believe pride and humility are mutually exclusive, but rather, they are completely independent virtues. Allow me to first offer an alternative, more delineating definition of pride and humility.

Defining pride:

In my view, Aristotle mistook the positive symptom of pride (confidence/self-respect) for pride itself. Confidence is not a virtue; allow me to explain. Notice how all other virtues are characteristics that you can choose. For example, one chooses to be honest, diligent, prudent, courageous, patient, temperate, etc. out of willpower. However, one cannot choose to be self-confident any more than one can simply choose to be happy.

I personally define pride as setting and living up to high standards for oneself, especially when it comes to strongly held principles; the positive side-effects thereof, such as self-confidence, naturally follow. Within the scope of my definition, pride also must come from within, for false pride arises from flattery and deceit, which are extrinsic.

How did I arrive at this definition from the Aristotelian understanding of “magnanimity?” I asked myself, why is a confident man proud? Because of achievement and proper conduct, which are in turn supported by setting and meeting high standards. From where else could one draw confidence if not through one’s own actions and achievements?

- For example, Michael Phelps clearly has just cause to be confident, supported by his unmatched record in Olympic swimming – it is safe to conclude that Phelps has set high standards for his swimming and then meets them through rigorous training.

- But make no mistake, one does not have to be an Olympian to have pride; proper and virtuous conduct suffices. Suppose an obese man one day decided to get into shape. The road is rough ahead, but he creates a schedule of exercise and healthy dieting and sticks with it. After a year of discipline, he’s reached his target weight. While he’s no Schwarzenegger, he should be proud that he set a high standard for himself and met it – the fact that he lost weight is only validation.

Specific examples of clearly defined standards include the Hippocratic Oath and the Journalist’s Creed, which exclusively feature high-minded virtues like sincerity, honesty, integrity, diligence, and, of course, pride as a professional. There are innumerable other professional codes of conduct and standards, but those are among the most famous. Doubtlessly, the physicians who hold themselves to the Hippocratic Oath and the journalists who hold themselves to the Journalist’s Creed can puff out their chests with pride and self-respect. Even on their deathbed, they will reflect proudly upon their adherence to those lofty standards. May those who violate these standards hang their heads in shame.

Both of those examples feature the virtues of discipline and perseverance. But is it possible for high standards to be divorced from virtue? I believe for pride to exist, it must necessarily be borne out of other virtues. In other words, the end does NOT justify the means; strict utilitarianism is wholly incompatible with pride. Suppose a man is aiming to become valedictorian (a lofty goal) by any means necessary, where no behavior, no matter how vile or ignoble, is off the table. Would there be any pride if he cheats his way to the top? For anyone who isn’t a psychopath, the answer is clearly no.

Defining shame:

Now that I have defined pride, I will define the corresponding vice – shame. Shame is either the failure to hold oneself to a high standard or failing to meet the standard set by oneself. Like with pride, shame comes from within. The feeling of shame doesn’t require a court of your peers but rather the court of self-reflection.

- In the case of failing to hold oneself to a high standard, consider a student who cruises through his education with little ambition, preferring to spend his days indulging in drugs, porn, and video games. While his peers aspire to and work towards greatness, he squanders his talents due to a lack of ambition (lack of standards for himself). Then one day, he wakes up and feels an intense shame, for he has done nothing with his life and wasted away his youth. There is no foundation from which to build his pride.

- In the case of failing to meet high standards set for oneself, consider again the obese man trying to lose weight, but this time, he only persisted for a month before slowly relapsing into old habits. Every scheduled workout session postponed with an exasperated sigh and every caloric limit dismissed with a wave of the hand. At the end of six months, not only has he made zero progress, but he gained even more weight in his negligence. Unlike the prior version, this man failed to live up to the standards he set for himself and thus feels ashamed.

Can pride be exogenous?

With pride conceptualized, let us explore some common contexts in which people say they’re proud of something other than themselves. Can one be proud of something extrinsic?

The single mother:

- Suppose a single mother works tirelessly to ensure that her children are not disadvantaged on account of an absentee father. She works multiple jobs so that she can afford the tools and services her children need to stay ahead in their studies. If her children appreciate their mother’s hard work and succeed through diligence, nothing shall make her happier.

- This example is a bit more complex, since pride here is seemingly contingent upon two parties rather than being intrinsic: not only does the mother need to set and meet high standards for herself, her children must succeed. Let’s look at a slightly different scenario to clarify.

- Suppose her children are instead ungrateful idlers who waste the tremendous effort their mother makes on their behalf. The mother still can feel proud of herself for striving towards such a worthy goal, but that pride will be overshadowed by the shame for her worthless progeny, right? But can we really claim that her shame derives from the fact that her children are such failures? We can dig a bit further – consider where the disappointed parent lays the blame: “I must have done something wrong to have them turn out like this; perhaps I should’ve been stricter.” Ultimately, she feels pride that she successfully performed her duties as a provider but shame that she failed as a guardian. That is, she blames their failure on her inability to meet her own high standards of guardianship.

- To prove my point, let’s take away the responsibility of guardianship from the mother – suppose the mother is a migrant worker who sends most of her paycheck back home to her husband and children. Here, she is purely the provider, not the guardian. When she finally returns home, she finds out that her husband gambled away the money and abused their children, resulting in them turning to drugs and delinquency. Could the mother really feel shame that her children became failures? She could not, by any stretch of imagination, blame herself for failing as a guardian, thus she has no grounds to be ashamed.

- For the sake of argument, suppose, in contrast, the mother was a hedonistic loafer, who spends all her days shooting heroine and abusing her children. To their eyes, her behavior and circumstance appear so abhorrent as to serve as an effective deterrent for degeneracy. And should they succeed, does the mother have any right to feel pride for her children? Should the mother show up at their doors, feigning a congratulatory tone, how well should her children receive her? After all, she has only ever been a hindrance. On the other hand, the children themselves have every right to be proud that they defied the odds by their own hands, because barring an orphan birth, few other circumstances are more inauspicious.

Racial, national, and cultural pride:

These divisive times, we often hear about racial pride, be it from minorities or from the alt-right. Is there any merit to being proud of one’s race? What does black/white/Asian/etc. pride even mean? In my view, racial “pride” and the typical nationalism are just expressions of tribalism. Little difference separates racial “pride,” typical nationalism, and allegiance to any particular sports team. Ultimately, if you’ve had no hand in the success of a certain race, nationality, or sports team, on what grounds do you have to feel pride? Merely from your inclusion within that group?

On the other hand, if inclusion in a group is contingent on upholding certain values, then there is just cause for pride. For instance, the US was founded on the ideals of respecting personal liberties, fiscal frugality, individual responsibility, and other elements of Protestant work ethic. The veracity of that statement notwithstanding, if someone believes it and tries to live up to those values, he will have just cause to feel pride as an American. After all, those represent lofty Renaissance ideals. Without meeting those standards, someone who’s “proud” to be an American merely rides the coattails of others.

Defining humility:

In contrast to my unique definition of pride, my definition of humility aligns much more closely with conventional perceptions thereof and thus I will keep things brief. My definition is simple – it is the acknowledgement of the inherent fallibility and shortcomings of oneself. From that basic postulate, many corollaries follow:

- Even the greatest will inevitably err and fail

- No individual nor group has a monopoly on good ideas or practices

- There will always be room to improve in one’s trade, craft, practice, etc.

- There will always be more to learn, and the humble can learn from even the unlikeliest places

- The subservience of the self to a greater ideal/principle/goal, typically subscribes to deontological ethics

Defining arrogance:

Whereas humility is the virtue, arrogance is the corresponding vice. I must note that like with pride/shame, humility/arrogance is not directly related to self-image. Since I define arrogance as the opposite of humility, then it must necessarily mean refusing to acknowledge one’s own shortcomings and fallibility.

- Believes himself to be superior to others in every way

- Boasts loudly about his accomplishments

- Believes himself to be infallible

- Refuses to acknowledge his own shortcomings or areas for improvement

- Elevates self-interest above all else, typically a consequentialist (utilitarian)

- Believes that the world owes him for merely existing

Pride/shame and humility/arrogance in relation to confidence

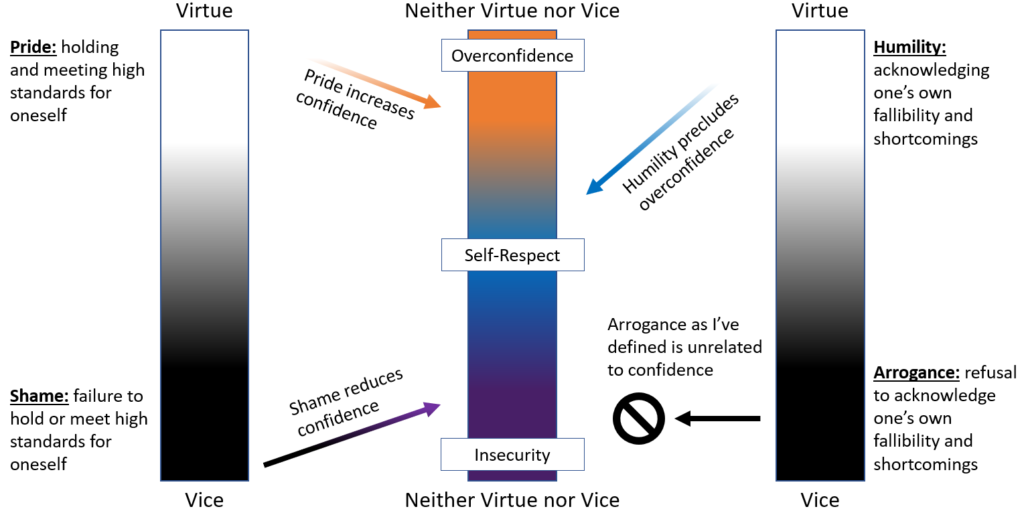

As mentioned earlier, the two scales pride/shame and humility/arrogance are not directly related to the scale of confidence. Confidence, or self-image, is a gradient whereby an excess thereof is considered overconfidence, while the deficiency thereof is considered insecurity. Note that this is NOT a scale of virtue, since one cannot choose to be confident the same way one can choose to be virtuous. One’s own subconscious determines confidence (I will write about this in a future post).

It should be self-evident that holding and meeting high standards (pride) will increase confidence, while the reverse (shame) will reduce it. When setting lofty goals and subsequently meeting them, confidence naturally rises. Conversely, when failing to set standards or proving unable to meet set standards, confidence crumbles.

The relationship between confidence and humility/arrogance is a bit more involved. By definition, humility precludes overconfidence, since acknowledging one’s shortcomings contradicts thinking too highly of one’s abilities – humility tempers the ego.

On the other hand, the usual definition of “arrogance” is strongly associated with overconfidence. In fact, even my definition of arrogance (the antonym of humility) may superficially appear equivalent thereto. However, it has no relation to the scale of confidence, for an overconfident man can be just as blind to his own flaws as an insecure man; the difference lies in how they handle those flaws.

- The overconfident man denies or dismisses his flaws in the timeless exhibition of hubris

- The insecure man hides away his flaws by: re-framing them as strengths, shifting the blame to external factors, overcompensation, avoidance, etc.

Intersection of pride and humility:

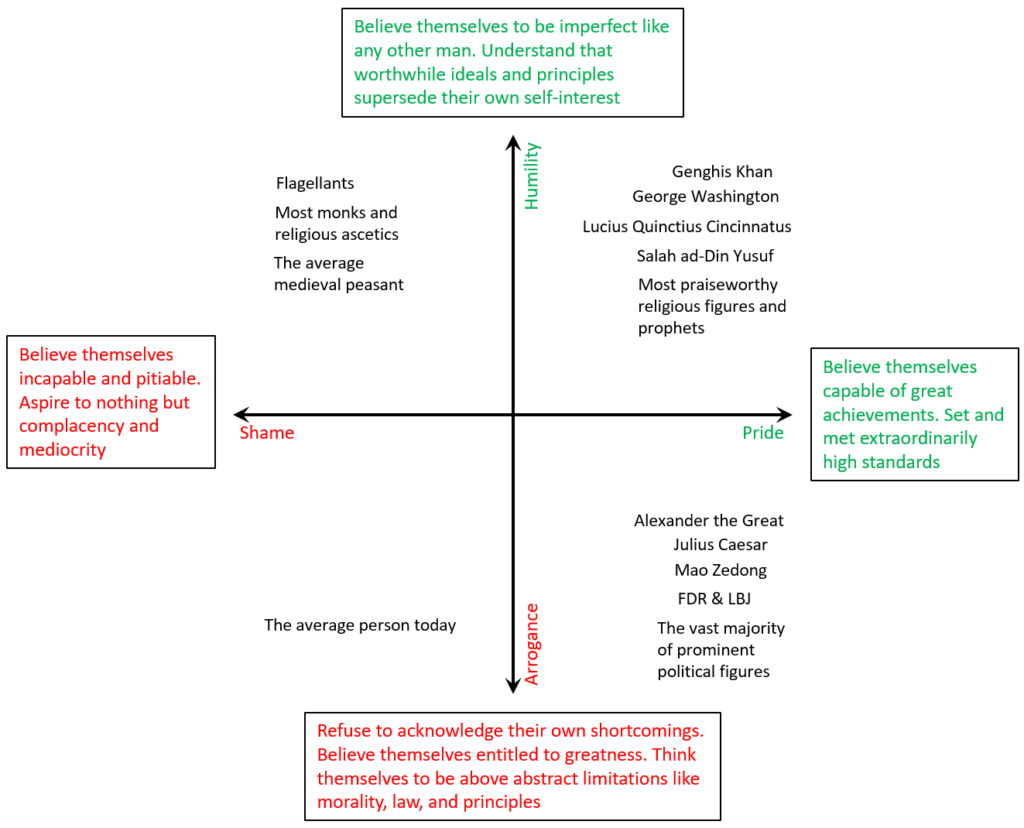

Now that I have defined both pride and humility, we can conclude from their definitions that these virtues are independent of each other, since holding oneself to high standards and meeting them do not relate at all to recognizing the fallibility and shortcomings of oneself. To drive the point home, I will provide examples of types of people who have different combinations of pride/shame and humility/arrogance.

Neither pride nor humility:

At first glance, it may seem that arrogance and shame contradict, for how is it possible to believe oneself to be simultaneously incapable and pitiable but also deserving of greatness and/or entitlements? Consider the average person, who is, by definition, mediocre. Consider how quickly he claims victimhood to circumstances beyond his control. Consider how much he idolizes success yet expends so little effort and takes so few risks. Instead, he concerns himself with trifling inconveniences and petty celebrity squabbles, reflective of how worthless he views his own time. After all, our life is only as valuable as what we choose to spend it on. If that’s not shame, then what is?

And yet…he also believes himself entitled to the world on a silver platter while offering nothing but his apathy in return. The average person demands instant gratification in the form of on-demand entertainment, quick/flawless customer service, rapid delivery of online goods, and so on. In fact, we’re at a point where people demand compensation for merely existing – I thought only deities were entitled to such treatment? How should I prepare my annual offerings to the exalted “average Joe?”

And if that weren’t enough, the average person cares little for high-minded ideals like honesty, justice, fairness, and intellectual integrity so long as he can pursue his self-interest. Everyone loves to claim that they are principled, but the average person is a consequentialist through and through. Consider how easily the average person judges another on breaking principles he himself doesn’t follow, how quickly he moralizes when he has nothing at stake. He also spouts his ignorant opinions with the conviction of a seasoned expert, caring less about truth than the self-gratification of being right. If the average person cannot even be relied upon to keep their word as a matter of basic decency and mutual respect, how can they be anything other than arrogant?

Pride without humility:

Without fail, the typical cautionary tale of hubris would feature a proud and successful person who’s eventually brought down by that vice; history is rife with examples thereof. In contrast with the humble, the arrogant believe themselves to be entitled to greatness and that their own self-interest are of such utmost importance as to supersede abstractions like morality, law, and principles. The vain tend to spend an inordinate amount of time worrying about their image in the eyes of the public, going so far as to making grand gestures purely for the sake of preserving their legacy rather than in pursuit of a greater good.

Arrogance can also manifest in the form of good intentions that pave the road to hell. It feels great and self-validating to offer aid to the misfortunate, especially if you believe that you know someone else’s best interest better than them. Take, for example, the Great Society programs that led to the welfare state. Economic outcomes aside, the mere idea of handouts debased recipients, since the act of benevolence implicitly takes power and dignity away from the beneficiaries to the grantor. Here, LBJ fits the mold of the proud, arrogant person perfectly. Was it possible LBJ truly cared about the poor rather than doing it for his ego? It’s impossible to say for certain, but his infamous vanity strongly suggested otherwise.

I must make a brief note here to delineate the arrogance of providing welfare and the arrogance of demanding entitlements. It may seem contradictory for both the grantor and beneficiary to be characterized as arrogant, but there’s more nuanced than that. In the former, welfare is not the status quo, so the act of the grantor to initiate welfare payments is possibly an exercise in arrogance. In the latter, welfare is the status quo, so the recipient is arrogant in demanding even more entitlements. Therein lies the difference between a “donation” and a “tribute,” whereas the former is when the great renders aid to the weak, a latter is when the vassal pays homage/fealty to their lord.

Humility without pride:

On the flip side, one would never hear about a humble man without pride, for he lives an anonymous and unremarkable life. Tyrants love ruling over these types of quiet, compliant individuals, for they aspire to nothing and know their place.

Pride and humility:

A proud and humble person is typically someone respected by many, for they likely exhibit a multitude of virtues beyond just the two aforementioned. This confident person not only aspires to greatness while maintaining high standards of excellence but also understands his own limitations as a human and strives to continuously improve even after achieving success.

If you know me, it should come as no surprise that the example I give would be my namesake, Genghis Khan, a man of great pride and humility. Given the sheer magnitude of his accomplishments, we know for certain that the Khan held himself to and also met extraordinarily high standards of achievement. Furthermore, he also held himself and his people to certain inviolable principles such as:

- Absolute adherence to diplomatic immunity

- Loyalty – insofar as when his sworn enemy was brought to his camp by that enemy’s own traitorous men, he had those soldiers executed

- All commitments and promises are honored

- All favors are repaid. His own coronation was much more about honoring and repaying his supporters for their contributions over the decades than his ascension to the title of Khan

- Meritocracy is held as an absolute; with the exception of a son as successor, merit and loyalty alone determined candidacy to all appointed positions

Remarkably, the Khan also embraced humility:

- He frequently deferred to his men’s expertise or delegated rather than micromanaged

- He recognized the weakness of his primarily cavalry-based army – he relied on the siege expertise of Chinese and Persian engineers

- He decided against invading India due to the hot and humid weather as well as the terrain – there was no ego, just an honest recognition of his limitations

- The Khan cared little for his personhood or material luxuries. He forbade any paintings or statues to be commissioned of himself. Nor did he hire poets to sing his praises across the empire. He only bothered to enter a single city, Bukhara, during his entire life. Those are both extremely unusual for a conqueror.

- He forbade an extravagant funeral – in fact, he ensured that his tomb would be nearly impossible to find such that it remains undiscovered to this day.

- He readily hired non-Mongol administrators to handle the day-to-day affairs of his empire, recognizing that civil administration is not his forte. “Conquering the world on horseback is easy; it is dismounting and governing that is hard.”

What about Washington and Cincinnatus? I hardly need to detail their accomplishments; I would rather highlight the humility in what they DIDN’T do. It’s said that absolute power corrupts absolutely, yet these two men resisted the temptations that would’ve ensnared lesser men and changed the course of history. Both Washington and Cincinnatus had the opportunity to permanently seize absolute power (Cincinnatus twice at that), yet both refused. They recognized the significance of their decisions and the precedent they would set; both put the greater good above their own self-interest.

Conclusion:

As described earlier, pride is setting/meeting high standards for oneself, while humility is acknowledgement of one’s own inherent imperfection, both of which are virtues. Despite popular conceptions of those two terms, pride and humility do not contradict, but can and should coexist. Whereas pride begets ambition, standards of excellence, self-confidence, and drive, humility tempers with caution, prudence, open-mindedness, and continuous improvement. Without humility, Icarus flew too high, against his father’s warning, only to be brought back to earth when the sun melted his wings. However, without pride, he never would have even gotten off the ground.